This post is by Expedition Leader Sangeeta Mangubhai.

It is the third day of our travels to the Phoenix Islands and we have now covered 700 miles of open ocean. We have already changed our itinerary to suit the currents and weather conditions and are heading directly through the center of the Phoenix Islands to Kanton Atoll.

We have been blessed with calm seas and good weather all the way out and the majority of the team got their sea-legs after the first day. [Seas were much rougher during the 2009 expedition crossing.] Four of us--myself, Rob Barrel (the owner and captain of the Nai’a and who been to Phoenix Islands five times), Tuake Teema (who is our esteemed Kiribati government representative) and Craig Cook (our doctor and safety officer for this trip)--have visited the Phoenix Islands before and were part of the original pioneering expedition in 2000.

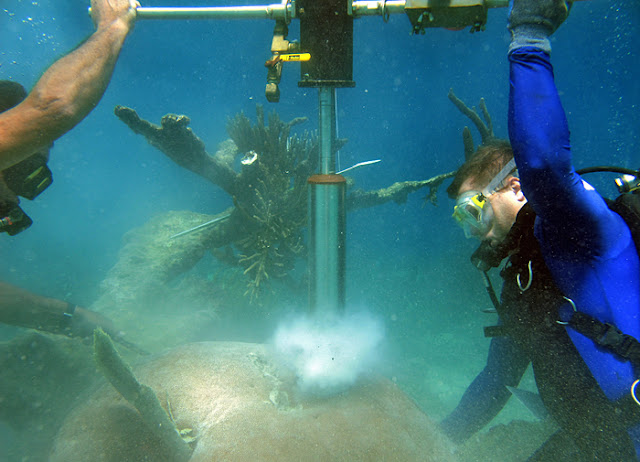

The others are new young up-and-coming scientists from WHOI, Scripps and KAUST visiting the islands for the first time. It is clear from talking to them, that they have a wealth of experience from other parts of the world and are experts in their field. Over the upcoming days, they all will be blogging and sharing a little of the research they are doing and how it will contribute to the growing body of information on the Phoenix Islands. [While in transit, the team has already started deploying data collection equipment called drifters.]

During the transit we have been sharing our local knowledge of the area of the team, reviewing our safety and biosecurity protocols, and we have started to prepare our equipment and datasheets. The team is now itchy and ready to get into the water and do their first dive in the Phoenix Islands.

In between talking to the team, I have had calm moments to sit and just reflect on the Phoenix Islands and what the place has meant to me. The Phoenix Islands changed my life and has inspired me over the last decade to work on coral conservation issues in the Pacific, East Africa and now SE Asia. The Phoenix Islands and the early expeditions we did in 2000 and 2002, are my “baseline” of what coral reefs should like in the absence of human impacts. It does not matter where in the world I work, the Phoenix Islands help me understand what a truly healthy reef looks like, if protected or managed well.

A healthy reef should been literally teaming with fish and invertebrate life against a backdrop of vibrant gardens of corals. It should be noisy and busy place with fish darting in, out and along the reefs. It should also be a place where large apex predators like sharks patrol the reefs in large numbers. As we get closer to the Phoenix Islands, I cannot wait to see how these reefs are doing. Part of me is anxious because I know how much the bleaching event in 2002/2003 affected the reefs. But the other part of me is hopeful that the fish populations are in a good condition and that there is much recovery.

-Sangeeta Mangubhai

P.S. And a special message from Rob Barrel (scuba diver) to any Rocket 21 kid reading this blog "we have arrived in Kanton and all the serious science has started so stay tuned."